- Home

- Seth Fried

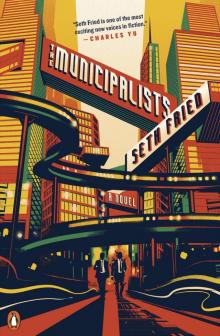

The Municipalists

The Municipalists Read online

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE MUNICIPALISTS

Seth Fried is the author of the short story collection The Great Frustration, named one of the Small Press Highlights of 2011 by the National Book Critics Circle. He is a recurring contributor to The New Yorker’s “Shouts and Murmurs” and NPR’s “Selected Shorts.” His stories have appeared in Tin House, One Story, Timothy McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, The Kenyon Review, Vice, and many others. He is also the winner of two Pushcart Prizes and the William Peden Prize. The Municipalists is his first novel.

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright © 2019 by Seth Fried

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Fried, Seth, author.

Title: The municipalists : a novel / Seth Fried.

Description: New York : Penguin Books, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018037814 (print) | LCCN 2018039255 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525505587 (ebook) | ISBN 9780143133735 (paperback) | ISBN 9780525505587 (ebook)

Subjects: | BISAC: FICTION / Science Fiction / Adventure. | FICTION /

Technological. | FICTION / Urban Life.

Classification: LCC PS3606.R5525 (ebook) | LCC PS3606.R5525 M86 2019 (print) | DDC 813/.6—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018037814

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Cover illustration: Matthew Taylor

Art direction: Elizabeth Yaffe

Version_1

This book is dedicated to Julia Mehoke and to the city that brought us together.

CONTENTS

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Acknowledgments

On August 7 of 1904, a flash flood hit the No. 11 Missouri Pacific Flyer as it crossed a trestle bridge on its way to Pueblo, Colorado. A wall of water carried off four of the train’s six cars and the remains of finely dressed men and women were found caked in mud as far as twenty miles away. The superintendent of the train’s dining service was in the forward sleeper when he saw the other cars go down and later offered the following account to the Colorado Springs Gazette: “I have never experienced anything like the awful sensation that came over me when I saw the cars, packed with human beings, floating down that flood. The water surged into the coaches so quickly there was not a sound from the passengers. I heard no calls for help.” Ninety-seven people were killed that night, making it the deadliest derailment of a long-distance train in US history.

The honor of second place goes to the No. 48 Lake Shore Limited, which jumped the tracks in western New York on August 12 of 1998. The train ran at full speed over a damaged length of rail, causing the first six cars to roll down a twenty-foot embankment and plow into an empty field. The rest jackknifed into one another and scattered themselves along the tracks.

I can’t help but remember the words of the man from the Flyer and imagine the scene as eerily quiet once the wreck settled. Torn steel. Clouds of dust rising up. Maybe at the edge of the field above the cottonwoods a flock of birds that had been startled from their branches by the sudden disaster were already beginning to circle back down to rest. Eighty passengers died that day, securing the Limited its second-place rank. If my parents hadn’t been on board, it would have only come in third.

I mention it because when a ten-year-old boy loses his parents, it makes him see things differently. So much of his world vanishes so quickly that he may be surprised to notice afterward that there are still telephone poles and traffic lights. The roads don’t peel themselves back in horror. The familiar buildings are all still standing. For instance, Becker’s Independent Grocery where he once walked alongside his mother. In his memory there’s the horsefly hum of fluorescent lights and his sneakers squeaking on the scuffed acrylic of butter-colored floors. The air is close with the round, earthy smell of produce and fresh bread. He remembers it well, but when he passes Becker’s on a gray day while sitting in the back of his foster parents’ dented minivan, the place seems to have forgotten him. The flat, glass storefront stares straight ahead without so much as a glimmer of recognition. Encounters of this sort at first feel like deepenings of the same loss, as if bit by bit the world was denying that the life he lost was ever real. If the boy is lucky, when the pain becomes too much, he will begin to see through this childish perception all the way to the truth. Then he will know what I know: The stubborn and impersonal resilience of the built world is in fact a force for good.

When the Lake Shore Limited derailed, it was rushing through the idyllic countryside of western New York. Any of my colleagues will tell you that victims of trauma in rural areas are far more likely to die before they reach the hospital than their urban counterparts. To see why this is the case, one doesn’t need to subscribe to the Journal of Demography and Health Care—though I do and can confirm it is an excellent publication. Rural health care administrators are dealing with a low number of calls spread out over large distances, and so are forced to reduce the quality of EMS care to achieve an acceptable cost per call. Keeping that in mind, it becomes clear that roads and buildings are not the villains here. The closer trauma victims are to population centers and dense infrastructure, the more likely it is that their lives will be saved.

It’s understandable why some people might still choose to strike out for the country, fleeing the frustrations that can result from so much proximity with other people. The choice can even seem obvious. Pavement and foul-mouthed strangers are traded for trees, a view of the lake, rolling fields. But the fact of the matter is that the farther you get from the infuriating crowds that might offend your sense of solitude, the more your risk increases. This is a notion you’re free to scoff at until the day that I hope never comes for you finally does, a severed finger in your beautiful kitchen, a drunk driver swerving the wrong way down a dark country road.

And believe me when I tell you that traumatic injury is the least of it. City dwellers have a lower risk of death from heart disease, cancer, stroke, drug overdose, and suicide. They enjoy more employment opportunities, transportation options, and cultural amenities. Contrary to popular perceptions, urban areas are also better for the environment than lower-density sprawl, and their school systems tend to produce better outcomes. That is the power of cities. The economy of agglomeration.

In the course of my profession, the important work I do, I fly to municipalities all over the country in the hope

s that they can benefit from my expertise. When I look out the plane’s window on a clear day, I can see both the cities and the sticks. Urban landscapes surrounded for miles and miles by a broad patchwork of empty fields. Never is it easier to see these two ways of life as physical realities in conflict with one another. The desire to come together and the desire to escape one another. Density and dispersal. It’s a war we fight with our own lives every day. And as long as I can remember, there’s never been any question about what side I was on.

1 In Suitland, Maryland, just outside DC, there is a large gray building that is home to the United States Municipal Survey. The main building boasts over 2 million square feet of assignable space. It houses research laboratories and data centers where our technicians utilize fleets of aerial drones to monitor most US cities in real time. In our Traffic department, serious men and women use VR rigs to investigate congested roadways, while down the hall the folks in Weather are busy running hurricane-force winds over manhole covers to determine at what point they get sucked up and turn lethal, cast-iron Frisbees whistling with a thud into the reinforced glass. Nearby there’s also the compound containing our supercomputer, OWEN, which ingests data from over two hundred satellites. Our headquarters is by all accounts an impressive facility, though my small office on the fifth floor is a bit more modest in scope.

There’s just enough room for a desk, two chairs, and a narrow bookshelf of binders. I find it cozy, but the lack of space can occasionally exacerbate an awkward situation. Like when Agent Marcuzzi stomped in that morning, taking a seat across from me without a word.

I had asked him to stop by for a friendly meeting, but his attitude was so immediately hostile that at 7:00 A.M. I was already forced to wonder what sort of day it would be. He hunched forward in his seat, causing the shoulders of his blazer to bunch. His hands were folded in his lap and he was knocking his thumbs together like he was waiting for a bus he didn’t want to get on.

He glanced at the model locomotive on my desk and I hoped for a moment he might smile. Next to my nameplate, I had placed a 1:64 scale model of an eight-axle C8 Manley & Wrexler. I had a reputation at the agency for being somewhat joyless and so I’d brought the model from home to liven up my workspace. It was from a series of collectibles called Trains of Yore, which depicted classic locomotives in scrupulous detail. They were generally marketed toward the elderly, but I was thirty-two and owned over two dozen of them. I liked the look of that handsome little locomotive on my desk and the C8 never had an accident while in use. So there was also an inspirational element. Yet when Marcuzzi saw it, he grimaced.

“I’m sure you know why I asked you to come.”

“No,” Marcuzzi said. “I have no idea.”

This surprised me.

“Fort Collins,” I continued. “You reported 4.73 percent added efficiencies.”

He nodded.

“The group’s goal,” I said, “was 5 percent per target municipality.”

“I know what the goal was.”

“Then you know that 4.73 percent is unacceptable.”

Marcuzzi let his mouth hang open, as if he couldn’t believe what he’d just heard.

“Thompson, are you joking?”

“About this? Of course not.”

“That’s insane,” he said. “That—that’s well within the margin. Those numbers are just to give you a general sense of—God damn it, I achieved my goal.”

“Peter,” I said. “On the projects I run, numbers are numbers. I asked you here so we could talk this through and get your efficiencies up.”

“A third of a percentage point? What do you want me to do? Head out to the wind farms and blow?”

“So you agree,” I said, “that making up the difference wouldn’t be hard to do.”

I had been trying to insert some humor into the conversation, but Marcuzzi must have read my smile the wrong way.

“Honestly, Henry. Go fuck yourself.”

He almost knocked over his chair as he left the room.

If I were less accustomed to this sort of friction with my colleagues, then a display of that sort would have been a minor scandal. But as it was I simply made a note to head out to Fort Collins myself at the first opportunity. I also took a deep breath and turned the C8 around on my desk so it faced me. In the cab stood a lone engineer staring ahead soberly, his little eyes taking in the seemingly endless plains to be traversed. I smiled down at the man. Yes, life wasn’t easy, but luckily there was always much to be done.

I’d blocked off an hour for Marcuzzi, so now there was time to attend the meeting for the Port Oversight Committee happening down on the third floor. It was hard not to regain your confidence when you were walking with purpose through the halls of headquarters. The speckled white granite floors were always polished and glassy, while the dark wood paneling along the walls gave the place a warm, collegial air. It was early still, but the broad corridors were already resounding with the dressy heel clacks of so many agents, all of us looking sharp in our matching, agency-issued suits—navy single-button blazers with thin lapels and the option of pencil skirts for any female agents who preferred them. I passed men and women gathered in the open work areas to discuss infrastructure problems. They rearranged 3-D projections of subway tunnels and took notes while model dams buckled from the force of simulated earthquakes. A group of junior agents passed me in a huddle, grabbing fist-sized data sets from their agency phones and tossing them onto each other’s screens as they argued among themselves about carbon emissions in the Rust Belt and the legalities of federal intervention.

The agency had begun seventy years back as a plucky arm of the DOT, a few dozen policy wonks who took pride in punching above their weight. But at the rate the world was urbanizing, cities had become the new space race. Our budget had exploded and we now coordinated with state and local governments to fund and advise thousands of major city improvement projects every year. We were in the middle of the golden age of American urban planning and for me the atmosphere of collective optimism never failed to produce a pleasant sense of belonging.

I remembered I had some fieldwork coming up in Wisconsin so I took out my agency phone and asked for the five-day forecast in Madison. The animation of a handsome young agent with startling blue eyes appeared on the screen.

“According to GPS,” OWEN said, “you’re at USMS headquarters in Suitland, Maryland.”

Our chief technology engineer, Dr. Gustav Klaus, had put a lot of time and energy into OWEN’s artificial intelligence interface, but the more humanlike the interface became, the more trouble I had interacting with it.

“I’ll be flying out later this week, just . . .” I held the phone closer to my mouth and half barked into it, “Weather conditions. Madison, Wisconsin.”

My voice was louder than expected and a fellow agent frowned at me as she passed.

“You sound stressed,” OWEN said.

The animation’s eyebrows arched slightly to demonstrate its concern. “While you’re in Madison, you should take some time for yourself and check out Lake Monona. It’s supposed to be nice.”

“The weather, OWEN, I just need to know the weather.”

“Oh, it’s the middle of June,” OWEN said. “I bet it’s gorgeous.”

I closed out of the interface in frustration. Between Marcuzzi and my own phone, the morning seemed off to a poor start. As I entered the meeting, I tried to focus on my eagerness to hear Agent Steinbelt’s report on Norfolk and the proposed regulations the agency would attach to any new funding. Steinbelt planned to start with a virtual tour of Lambert’s Point and so we were in the windowless central boardroom with one of the better 3-D projectors. I took a seat at the long conference table and told myself there was time enough for this day to be a good one. A productive one.

But almost as soon as Steinbelt brought up the simulation, the projector sputtered out and the wate

rs that had just begun to lap at our feet faded from the room. The fire alarm let out a single shrill whoop and then went silent as our agency phones began to emit a high-pitched tone. The devices lit up the dark room as committee members removed them from their pockets and briefcases. The screens all displayed a dense block of characters:

!#~#K#~y1878~#@#~#!/!#~#@#y#!9!#~#@#~#!

!#~#@#~#!%!#~#@`~#!8!#~#@#~#!%!#~#`#~#!

!#~#@#~#!%!#~#@`~#!8!#~#@#~#!%!#~#`#~#!

!#~#@#~#!%!#~#@`~#!8!#~#@#~#!%!#~#`#~#!

!#~#@#~#!%!#~#@`~#!8!#~#@#~#!%!#~#`#~#!

!#@#~{LA_URBOJ_ESTAS_FROSTIGITAJ}~#!

!@^!~.>Kt&*`87@/8^8Kt%!#~#@#~9P/{788##!

!87@/~#!%!#~#@87@/~#!%!#~#@@/888Kt&*!

!@^!~.>Kt&*`87@/888Kt%!#~#@#~9P/{888##!

!#~#K#~y1878~#@#~#!/!#~#@#y#!9!#~#@#~#!

!#~#@#~#!%!#~#@`~#!8!#~#@#~#!%!#~#`#~#!

!@^!~.>Kt&*`87@/8^8Kt%!#~#@#~9P/{788##!

!87@/~#!%!#~#@87@/~#!%!#~#@@/888Kt&*!

I stared down at the message in confusion while the other committee members held up their phones like flashlights and shouted questions to one another.

I excused myself and hurried out of the room to report the issue to a technician. In the hall, the sunlight coming through the windows only emphasized that the whole building had gone dark. A few nearby faces were illuminated as agents examined their phones. Elsewhere people flipped unresponsive light switches and tapped the dead call buttons on elevators. Some half leaned from their office doors as if waiting for someone to wander by with an explanation. Meanwhile, shouts began to come from behind the doors of the secure rooms whose passcode-protected entryways were sealed shut without power.

The noise from my phone grew more piercing and then abruptly stopped. I held it up to check the screen and it exploded. There was a flash of sparking blue flame and something hit my face like a fist. All at once my palm was bleeding and there was a sharp pain in my cheek. The hall was filled with the smell of burned plastic and I felt dizzy. All around me there were blurred figures stumbling forward and covering their mouths or clutching their hands to their chests. The shouts from the sealed rooms grew more frantic and I could hear people begin to pound on the doors.

The Municipalists

The Municipalists